Left Vs. Right

Here’s Part 2 of a multipart collection of my thoughts on all things music and what I’ve learned as a student and teacher over the last few years. Here’s Part 1 for those interested.

Two Brains

Besides Kenny Werner, several other thinkers and musicians wiser than I have helped deepen my understand of all this music stuff. I was turned onto Iain McGilchrist, psychiatrist, writer, and former Oxford literary scholar, through the YouTube algorithm. Drawing from much research and a wide spectrum of disciplines, McGilchrist has extensively written on the left and right hemispheres of the brain and the vastly different perspectives they have on the world. To summarize:

In McGilchrists’ view:

Qualities associated with the “left” brain include:

A penchant for ‘grabbing’ things, ideas, information, etc. The left hemisphere is literally responsible for the movement of the dominant hand for the majority of people.

Quickly sorting and characterizing things into logical groups.

A desire to control and manipulate the world.

A responsibility for language and fact recall.

Tends to eschew nuance for a “no, but” approach.

The right brain, in contrast:

Tends to view the world in a wholistic, contextual way.

Is responsible for integrating the specifics collected by the left brain into a larger framework. Damage done to the left hemisphere of the brain can still allow someone to live a mostly normal life. Damage to the right, however yields one’s understanding of the world irreparably broken, leaving one incapable of living a normal life.

Often plays a devil’s advocate role, reminding us there are likely variables we don’t know but have to consider in our decision making.

Tends to allow for and understand diversity and complexity, responds with “yes, and” to an inquiry.

McGilchrist argues both hemispheres are crucially important for life, though for both hemispheres to work in concert, the left must serve the right hemisphere. Our ‘grabber’ brain brings us things to parse over, work with, and characterize, while the right brain contextualizes and supervises the work of the left, often having to temper and redirect the overall collaboration. He argues that much of our societal and individual trouble in the modern era is due to an increase in left-brain dominant perspectives, and I think he’s spot on. One can look for example to politics alone and immediately see a vacuum of a right brain perspective. How many of us citizens clamor that our politicians are simply squabbling over the wrong issue instead of taking issue with the extremely adolescent, tunnel-vision tone of the entire process.

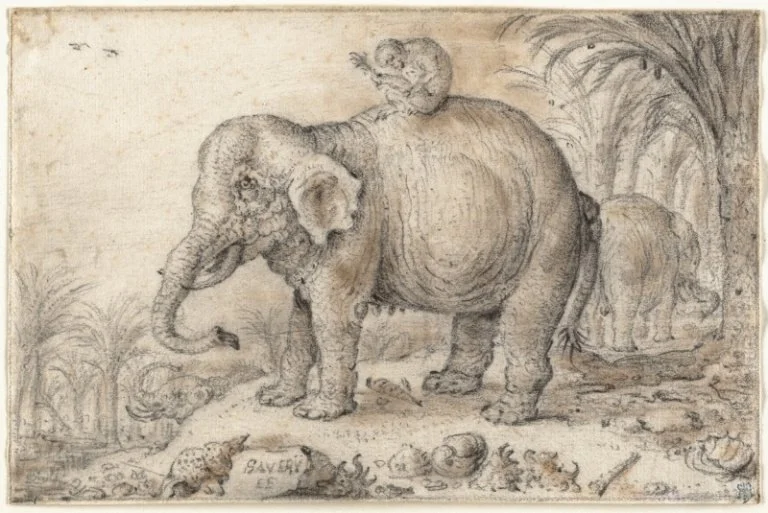

Another related metaphor sometimes used is that of a monkey (left brain in this case) riding an elephant (right brain). The monkey thinks he’s in control, attempting to direct the elephant in a commanding voice. In reality, the elephant has all the control, yet doesn’t feel the need to say as much. The elephant can be directed, but it’s a slow process, a process the monkey must grapple with. Besides, the elephant is the wiser of the two.

Much of my musical troubles, upon reading McGilchrist, were so clearly left-brain-heavy approaches. I had grabbed much information and many tools along my musical journey, but struggled to integrate them in a contextual way.

As a player and teacher, I’ve been practicing at getting these two brains working together more in sync. For different kinds of musicians, this balance can look different, but there are some generally healthy perspectives that are common across the board.

Many of the common impediments I see students struggle with are things like:

-not being able to learn songs on their own

-inconsistent or bad rhythmic feel

-not knowing how to practice

-not interacting with music in a more linguistic way (using numbers and thinking relatively)

-trouble playing by ear

-reading fluently

-not having a framework that’s scaleable to accommodate for endless musical growth and appreciation

-struggling to consistently enjoy and be gratified by the wholistic process of learning, playing, and listening.

All of these problems start to dissolve with a stronger right brain approach.

In my experience, the right brain can “check” and direct the left brain, but it’s also more like both approaches must work together while you supervise your practice, a bit removed from being immersed in any particular thing.

Left/Right Balance in Learning Music

Say someone’s learning The Beatles’ Here Comes The Sun (picked because most of the Western world can hum that pretty easy) with a few different methods.

A strictly left brain approach for someone who is new or newer to music might look like:

Learning by rote (by watching a tutorial). Someone showing you what to “grab” immediately is often the most effective way to learn a particular tune.

Using tabs for guitar or something like Synthesia for piano (showing the piano keys that are played).

If they have more of an aural leaning, they might use their ear to correct missed notes or chords, not quite knowing exact stuff but knowing when something isn’t right.

Those who have never automated a fine motor skill before might heavily focus on their individual movements and struggle to find any physical or mental ease or relaxation with the instrument.

A more advanced musician learning the same song from a left brain approach often would utilize:

A more detailed approach, by rote, by perhaps a transcription of the music.

Sheet music- if they were an “eye” player, vs. an “ear” player. Many pianists fall into this category.

Music Theory- if a player knows this song is in A Major, that can help contextualize and “check” the song as they learn it.

Knowledge and Familiarity with Instrument- if a guitarist can hear that the guitar sounds capoed up the neck, and they recognize the specific voicing of the D chord, that can further help them learn quickly.

Specific gear, techniques, or similar aesthetic details to help emulate the song.

Opting for learning in a more specific way as opposed to taking liberties.

All these methods commonly work, and accomplish the task at hand- learning “Here Comes The Sun”, but often nothing deeper. Before looking at some right brain learning methods, we can fine-tune the left brain’s way of learning in a way that will accommodate a right brain approach.

Optimal left brain learning methods can often look like:

Doing it right the first time. Learn a song slowly and carefully, little bits at a time if needed. The left brain is in charge of fine-motor skills and will ‘grab’ a song with stunning accuracy and efficiency if slowly and clearly shown. Mistakes from attempting to learn too quick provides many incorrect “whats” for our left brain to work with and leaves little chance of acquiring any mastery.

Training and then letting the body play. Working on a piece of music (and anything) in a way that promotes physical mastery of it. This entails doing things like not looking (even closing ones eyes), losing tension, and of course going slow to aid in accuracy. Kenny Werner likens optimal music practicing and performing to using a fork or brushing your teeth. Can you feel the ego bristle at such an absurd comparison? Yet all of us are masters of using a fork and (hopefully) brushing our teeth, expecting we’ll automatically attend to both activities daily. Such indispensable practices have long ago moved from the mind to deeper within the body, where they perform themselves. It’s only because music or other arts can come with an heir of seriousness (per the ego) that we don’t pursue muscle memory in a similar way.

Learning in rhythmic context (in time). This is crucial due to our left brain’s penchant for doing physical motor skills with regularity. This is the flip side of learning slowly/carefully, always (with some exceptions for certain musical situations) play in time. This is a left and right brain issue, but understanding the damage of practicing and playing out of time directly affects the specific piece of music in maybe the most noticeable way. Music is nothing if not consistent, and this muscle can be excercised in every single musical situation.

Learning in digestible chunks. Short, hyper-focused practicing that expands our awareness and grasp of what the left brain is grabbing. This entails paying maximal attention while coming at a task from many different angles, looking for any weaknesses that might pop up.

Employing the mind along with the body. A deep mental and aural (ear based) familiarity with musical concepts comes from focused practice. This enables practice away from the instrument, which is a game-changer. Our inner grabber brain will work in the background if we give it tasks to attend to. Being away from your instrument is in invitation to review the specifics of whatever we are working on. As Kenny says, reframing difficult or challenging music as simply unfamiliar can profoundly turn the tables on our progress.

Though these immensely healthy methods quicken the learning process, many left-brained heavy players, beginner to advanced, never deepen or maximize the how of their learning are unable to refine and promote the overall mastery of playing. That’s where the right brain can help.

Finding Balance

A strictly right brain approach to something is rather incomplete and hard to articulate. It’s perhaps akin to that one friend who has what sounds like a brilliant idea but zero plan on how to implement it. It’s often been where I find myself in composition, hearing fleeting moments of profound beauty in my head, but not finding the right notes or chords, or even the simplest of starting points to articulate it. For many people who can hear when something isn’t quite right in music but can’t put a finger on what it is, or how to even begin to improve it, we should suspect the right brain, daydreaming for some unknown ‘what’ to give life to the ‘how’.

When the right brain shines is when it has something to oversee and some specific things to work with provided by the left brain.

“Both Brain” Practices:

The below practices were the things that helped give me a workable framework to guide my progress in all the stuff I play. These techniques can help marry the specific musical tools with with the wholistic musical habits we are overall deepening.

Starting with and using what you have (and be consistent). When we put external qualifiers on what our music should be, or how it should be made, we tend to have little or no success with it. When seen as a gift, any success one has with music feels like a net positive; moreover, whether or not there is even success is a moot point- we should play and learn because we enjoy the overall process.

That is all pretext to say: there is no amount of facility, gear, or knowledge that you are lacking stopping you from getting to where you want to go, except for maybe a workable framework and attitude for longterm learning. This is often a bitter reality that we (I’m referring mainly to me) need to accept regularly.

There is nothing wrong with using specific tools to aid in our enjoyment and learning process. That being said, there can always be an excuse for not doing some honest practice and self-development with the tools available on a daily basis. My experience with the hobbies that I regularly invest into (music, cooking, getting beat at online chess) is that committing to at least daily interaction with it (albeit for only a handful of minutes some days) is transformational. Our ego might hate that its as simple as practicing daily, but it is. I like to remind myself regularly: we naturally get better and more familiar at whatever we practice, for better or worse.

Thinking in the key of “music”. Learning and reviewing the harmony (chords) and melody (notes) of the song without exception in context of the key. This means thinking in numbers, and it’s the quickest way to become harmonically fluent. The left brain grabs onto specific notes and chords and it’s the right’s job to remind us that music is always relative. Thinking in numbers- (1 1 4 5)- being the verse of Here Comes The Sun) puts a label on the sound of the 1 chord (the home, resolved feeling), 5 chord (away, tension chord), etc.

Lots of musicians know this stuff only in their left brain (and even then not from familiarity but memorized) but it needs to become real and embodied. Your right brain needs to remind you that you can practice ear training with all music you encounter, even the tune the washer plays after a finished cycle. It just takes a little attention and regular practice. A good ear makes music automatic (it’s how I cheated in piano lessons as a kid). With enough practice pretty much every popular song’s specific chords and notes will immediately be generally recognizable (easily being able to recognize the home chord and general harmonic movement), and with enough context practice on your instrument, easily playable.

With time, numbers can be as obvious and easily heard as colors are to see. Beautifully, most music all starts to sound in the same key- not actually the same pitch, but so easily recognizable using numbers that they might as well be in the same exact key. I often tell students I wouldn't be mortified to forget how to play guitar or piano (though those are giant parts of my life), if I still had access to all the ear training I’ve done- in grocery stores, while getting gas, or wondering what pitches my email alert on my laptop was made with. Things you practice eventually totally automate themselves, and now I can’t turn it off! Ultimately, this process transforms music into a language, ready to communicate and be understood at the same depth as a native language. Like someone with a command of language, a good ear is ready to communicate and understand. This does more than anything else to make music automatic.

Learning to let rhythm guide your entire practice. A rhythm that doesn’t land right will always be more out of place than a missed note or chord. Like our ear, rhythm can be constantly practiced. Feeling it is the body’s responsibility, and just like harmony it can be automated without thinking about it.

The rhythmic context of a piece is paramount. Playing at a consistent (often slower) rhythm is crucial to scale up the piece and overall rhythms at any tempo. Practicing feeling 8th notes in one song is strengthening our general rhythm for every song. This muscle must be strengthened and so deeply absorbed that it moves from the mind into the body.

Automating rhythm could mean mastering notated and/or improvised rhythms (or both!). Rhythm can be one of the giant habits missing in stagnant practice sessions, and helps provide focus and context to everything we practice (plus, it pairs with everything else in our practicing). Not to mention, involving the body to feel rhythm, to lose itself in it, is as sublime an experience as it is primal.

Meeting in the Middle. If musical success and enjoyment is the goal at the peak of the mountain, it can feel like it’s only new knowledge, experience, techniques, gear, or plain luck that can get us there.

For me, musical self-acceptance was the missing layer of my practicing that kept every inch of progress a struggle. We’ve all heard ‘joy is in the journey’ but that’s only made any real sense for me until recently. It’s a paradox, and a big one. The more I practiced self-acceptance, the more empowered I felt to realize the goals I had of conquering the unnatural and unfamiliar. The two: self-acceptance (learning to dig the sounds I make now) and self-betterment (mastering the craft of making sounds) meet in the middle to get where we feel compelled to go.

An aside: I can hear Kenny Werner in my head (after having ingested a whole lot of his ideas) point out that musical self-acceptance is its own absurdity. Identifying with your music isn’t required to love it, play it, or respect it. Kenny goes farther than with an example: simultaneously talking to a class while playing piano. He asks the class if he isn’t attending to the music-making then who is responsible for it, or as he puts it “where (or who) is the music coming from, if not me?” He posits that it’s the students’ job to answer that question. No matter the source of our creation, feeling like you are an instrument that is passively watching your hands work is a place one can work from indefinitely.

Nothing Special About Music

As one progresses with a healthier balance of these two perspectives, you aren’t just learning/practicing/playing one thing, but music in general. Though in my experience there is really nothing inherently musical about any of these concepts, rather this is what learning holistically looks like. No matter the subject matter, there is the specific that we must integrate into the general without getting sidetracked by it. There is additionally the ego that must be held at bay while the adult in our head (right brain) directs how to go about the daily process of learning. The subtitle of Kenny’s most recent book Becoming the Instrument is “Lessons on Self-Mastery, from music to life”. I am starting to witness this in my life, that musical lessons and techniques will spill over into other areas that need attention and improvement. The study of music (and everything else artistic) can become an inconsequential way we can practice living better lives, which in turn might enable us to make more effortless music.